Hoping for A Return to Normalcy Has Felt More Like Waiting for Godot

In Samuel Beckett’s famous play, two men meet near a tree, discuss various topics, and reveal to each other that they are waiting for a man named Godot, who never arrives. Since the Great Recession nearly 14 years ago, bankers and investors have eagerly awaited a return to “normalcy” – the word is in quotes because it’s been so long that it’s tough to say what normal is anymore. As in Beckett’s play, it’s fair to ask whether “normalcy”, like Godot, will ever arrive. We’ve waited for a more “normal” interest rate environment, a return to traditional business and market cycles, and less fiscal and monetary intervention in the economy and markets – all of which we hoped would translate to fewer market distortions, which have unfortunately become more commonplace.

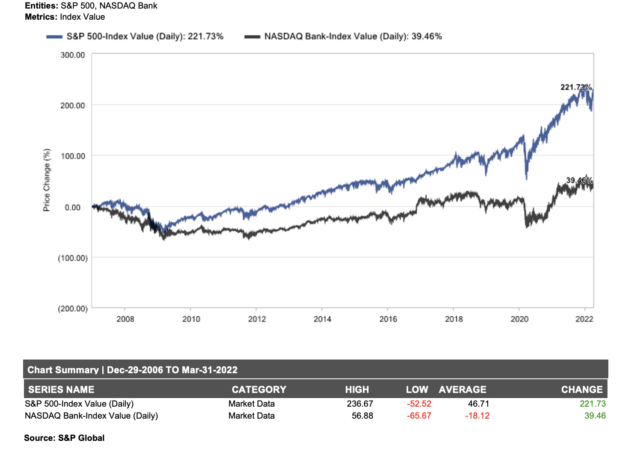

Every year since 2008, the consensus view has been that a return to “normal” is just around the corner. And while it hasn’t come to fruition, there have been a few head fakes, most notably for about 18 months or so after the 2016 presidential election, when the promise of higher rates, tax reform, and less regulation drove bank stock indices to record highs by mid-2018. But what came next? A punishing market decline in the second half of 2018 – led by bank stocks – followed by a fairly uneventful period of malaise, which of course preceded the disastrous events of early 2020 with the onset of the pandemic. So maybe others feel differently, but it’s seemed to us as though we’ve simply lurched from crisis to crisis. Some very real, like COVID, but others were seemingly more a function of changing market structure, dislocation, and the implications of changes in monetary policy, than anything else, like the brutal and mostly unanticipated market sell-offs in mid-2011, late 2015/early 2016, and late 2018, late 2015/early 2016.

Bank Stocks Have Underperformed the Broader Stock Market

Will This Time Be Different? Maybe…

There was, and still is, a case to be made that this time could be different. The hope is that the process of reopening the economy, pent-up demand, a period of controlled inflation, and higher long-term interest rates coupled with a steady dose of short-term rate increases would translate to an almost a Nirvana type of macro backdrop for bank fundamentals, and by extension, for bank stocks. Layered on to that, and certainly unique to this cycle, was the view that unprecedented levels of excess liquidity from fiscal and monetary policy actions taken over the last few years would take longer to drain off bank balance sheets, producing the added benefit to banks of a slower increase in funding costs, as asset yields presumably rise more quickly. The end result, in theory, is that margins would expand, reclaiming at least a portion of the precipitous drop in bank margins since The Great Recession. And voila – we would finally see some semblance of a return to normalcy.

As we approach the end of Q1, it’s fair to ask, in light of recent developments, if the scenario above is still likely to play out. Below are our thoughts, some questions we have, and what we’ll be looking for from Q1 results and earnings conference calls.

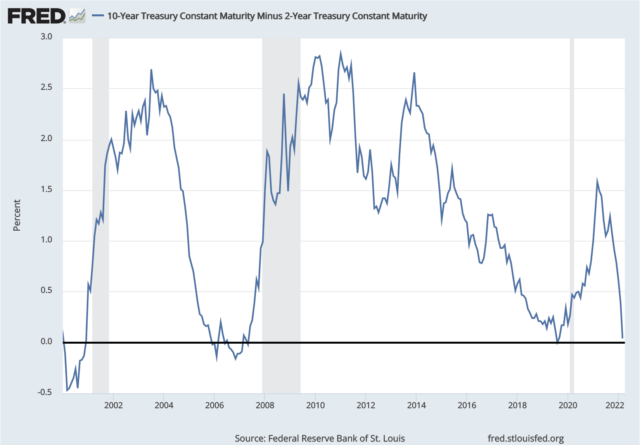

- A tug of war between higher rates and the implications of a flat/inverted yield curve. Higher rates on an absolute basis are undoubtedly a positive for most banks, as are the implications of the extraordinary level of excess liquidity sitting on bank balance sheets. Historically, in the early stages of a rate hike cycle, increases in deposit costs tend to lag asset yields anyway. The benefit of this extended lag process during this cycle should be outsized. The caveat, of course, is that never in our experience has the yield curve inverted right at the start of an up-rate cycle. Given the historical accuracy of yield curve inversion as a predictor of an economic downturn, recession fears are mounting. Typically, in response to an inverted curve and evidence of pending economic weakness, the Fed would at least start to signal, or outright begin the easing process, but is obviously hamstrung this time by inflation.

So which side will win the tug of war? On the one hand, from our analysis, roughly two-thirds of the spread income benefit for the largest banks is driven by increases in the short-end of the curve vis-à-vis the long end, suggesting that we maybe shouldn’t overreact to a slightly inverted curve. On the other hand, will the fundamental reality be outweighed by collapsing investor sentiment brought on by even the prospect of looming recession, the onset of credit problems, and the perceived need for an increased reserve cushion?

Yield Curve Inversion Has Historically Been A Precursor to Recession

- Are costs under control in light of inflation pressures, tech spend, the war for talent, and The Great Resignation? One of the more disappointing aspects of Q4 2021 results and the commentary on earnings calls was the extent to which inflation pressures had already seeped into bank operating budgets for the coming year. In retrospect, given the news flow in the months preceding the earnings release, investors (including us) probably shouldn’t have been as surprised as they appeared to be (judging from the market’s reaction). Inflation-driven expense increases are in addition to cost pressures resulting from stepped-up tech-related spending, and the war for talent generally as people nationwide adjust their priorities and lifestyle choices post-pandemic. The question is the extent to which higher-than-expected expenses eat into added profits from widening margins.

- Not likely an issue just yet, but keeping a watchful eye on credit. To be clear, we aren’t seeing overt signs of credit distress just yet, employment statistics paint a fairly rosy picture of the job market, and the absolute level of long-term interest rates – which are basically now back to pre-pandemic levels – don’t strike us as quite high enough to spark concern. That said, higher inflation tends to initially sting lower income borrowers most, as food and energy costs soak up a relatively higher percentage of take-home income, with obvious implications for discretionary spending, and eventually and more ominously, for the ability of these borrowers to service existing debt. Recession fears – whether perceived or real – also can impact sentiment across a wider spectrum of businesses and people, as the inclination to begin to hunker down takes hold. A more technical accounting issue is the extent to which we might hear on earnings calls about the approach to provisioning and reserve build as macro conditions change, in light of the implantation of CECL.

Again, we don’t expect any material surprises in either Q1 results or in the commentary provided on earnings calls, but we do wonder if it’s time to start battening down the hatches a bit in certain areas, particularly for those lenders outside the regulated banking system whose chops are untested in a true downturn (COVID doesn’t count, given regulatory forbearance). This is a topic we’ll be delving into more deeply in a future article.

- Is M&A likely to heat up? A smattering of M&A announcements recently – the big one being the tie up between TD and FHN – coupled with a number of smaller deals, suggests to us that the recent slowdown in M&A announcements and regulatory approvals could be coming to an end. We won’t rehash the details of what appeared to be behind-the-scenes drama at multiple regulatory agencies late last year, but it does seem clear that uncertainty about the regulatory process and the extended timelines for deal approvals weighed on the minds of banks seeking to move forward with M&A. To us, the macro backdrop, healthy bank stock valuations, and favorable “deal math” (with larger banks again trading at premiums to their smaller brethren) seemingly set the stage for a flurry of deal activity in the second half of last year and earlier this year, but this hasn’t yet materialized. We also wonder to what extent recessionary fears so soon after COVID might prompt tired bank management teams and Boards of Directors to make sure they don’t miss the window to sell ahead of the next downturn.

- Sector stock prices have been more sensitive than the general market to geopolitical concerns. While very few U.S. banks have direct exposure to the conflict overseas, the reverberations have been disproportionally impactful to bank stock prices relative to other sectors and the broader market. Bank stocks have markedly underperformed since the start of direct conflict between Russia and Ukraine. Though recently, the rationale for bank stock underperformance has been a little more muddled, as curve inversion and domestic recessionary fears are added to the mix of concerns. Commentary on Q1 earnings calls is likely to be limited to the anticipated ancillary impact to banks from the war (e.g. the implications of higher oil prices; supply chain interruptions; cyber attack readiness, etc.).

- Valuations strike us as relatively undemanding, all things considered. In thinking about the stocks, there are several challenges. First, is simply perception and sentiment, entirely around the economic outlook and the shape of the yield curve, to which banks are clearly more sensitive than most. Second, should geopolitical strife continue, bank stocks are likely to remain range-bound, with a rally likely on the heels of a concrete settlement and downside risk should there be new negative developments or perhaps simply if it becomes more evident that the war will be prolonged. Third, banks will likely be challenged to grow tangible book value all that much this quarter in light of the mark-to-market impact of higher rates on investment portfolios, a dynamic that strikes us as somewhat underappreciated heading into earnings season.

Balanced against these negatives are several notable positives. First, mid-quarter updates from larger banks have been generally strong, with several increasing previously issued earnings guidance, suggesting that perhaps the U.S. economy will prove resilient than current sentiment would seem to suggest. Second, the early stages of an up-rate cycle tend to be a powerful catalyst for bank stock prices, with the caveat of course that we are in a bit of unchartered territory given yield curve dynamics and recession fears. Third, valuations, particularly following a recent rough patch for bank stock prices (KRE down nearly 6% month-to-date), strike us as pretty reasonable, and reflective of many of the challenges noted above.

If we seem a little unsure about how it’s all likely to play out, that’s because we are!

If we seem a little unsure about how it’s all likely to play out, that’s because we are!

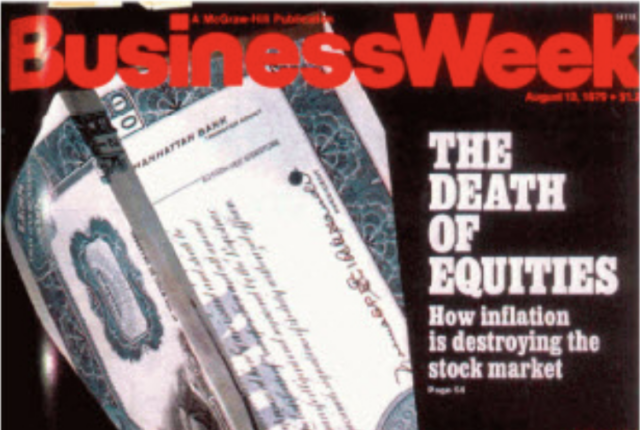

We would view with skepticism any forecast or forecaster that purports to know exactly how the coming months are likely to play out. Mark Twain noted that history doesn’t repeat itself, but if often rhymes. However, we’ve struggled to recall a time quite like this in our two+ decades following banks. From our reading, the closest parallel to the current situation would seem to be the decade of the 1970’s, when, following massive spending programs enacted in the late 1960’s, a devastating war, and an oil shock, the U.S. economy was faced with a sharp increase in inflation, a sluggish economy, and flat equity markets for an extended period, eventually prompting the infamous article on the cover of Business Week in 1979 lamenting the “Death of Equities”. We’re not suggesting the end result this time will even be remotely similar, but rather highlighting how unique this period of uncertainty is, in the sense that we have to go back nearly 50 years to find even a remotely relevant parallel. One thing is for sure, and that is that Q1 certainly won’t be a typical, garden-variety earnings season.