We’ve noticed a recurring theme in meetings between bank stock investors and bank management teams over the past several months.

In recent months, commentary from regional and community bank management teams in conversations with investors has been uniformly positive. Local economies are healthy with employment resiliency, loan growth remains solid (if not robust), deposit outflows have been slower to materialize than anticipated, margins are up, and there are no indications of material credit-related stress. When pressed on the outlook, bankers acknowledge the potential challenges ahead, including the darkening macro picture, negative news flow, and the reality that it simply takes time for recent actions (like rapid interest rate hikes) to filter through the system. That said, discussion of the challenges seems more hypothetical in nature, rather than a reflection of what bankers are seeing in their day-to-day business and local market economies today.

Investors understandably push back on this narrative, citing unprecedented macro uncertainty (inflation + higher rates + QT + geopolitical conflict), and warning signals from the stock market (which tends to anticipate what’s ahead before it’s clearly apparent), in essence implying that something, somewhere must be amiss, if not now, then just ahead. Clearly, these concerns did not manifest in Q2, which was one of the strongest periods for bank fundamentals that we can recall in some time, and they don’t seem likely to rise to the surface during the upcoming Q3 (and perhaps even Q4) reporting period either.

Following these industry events and meetings, bankers and investors leave with their opinions seemingly intact, but perhaps with somewhat less conviction than they had going in, given the divergent viewpoints from those on the other side of the table.

Stepping back to a prior era, diverging viewpoints like what we’re seeing today seemed less common…

Banks have historically functioned as a reasonably good proxy for the economy and, by extension, for bank stock prices. Key operating trends for banks, including loan growth, margins, and asset quality, tend to reflect the underlying pace of current economic activity, the shape of the Treasury yield curve (which in the past has been a reliable predictor of the future economic environment), and current and potential trouble spots in the economy (in the form of charge-offs and nonperforming/delinquent loans).

Prior to The Great Recession, this linkage was very direct and highly predictive. As a bank analyst during this period, I always felt in digging through bank balance sheets and talking to bank management teams I had a bit of a predictive edge over most other sector analysts in assessing the economy. Healthy employment, strong corporate balance sheets, solid GDP growth, and a steep yield curve were reasonable proxy indicators for robust bank stock fundamentals and healthy bank stock valuations. The reverse was also true, as slowing economic growth, a flat-to-inverted yield curve, increases in unemployment, and emerging problems as indicated by rising loan delinquencies provided ample warning of potential troubles ahead. As it relates to the stocks, while there was some element of lag effect in both directions, large scale material surprises were rare, with stocks generally performing as one might expect given the prevailing economic and market backdrop at the time.

…and we suspect we might know the reason why

Since The Great Recession beginning in 2008, however, this direct and predictive linkage to bank stock performance has become increasingly unmoored. Sharp market sell-offs, often led by bank stocks, specifically in late summer/early fall 2011, late 2015/early 2016, and late 2018 were not preceded or followed by fundamental developments within the bank sector that provided advance warning or justification after the fact for what occurred in the market. What we did know was that bank stocks in particular were uniquely sensitive to these market developments and that they diverged from the sector’s operating fundamentals. In fact, when we were contemplating starting our investment fund a few years ago, we considered this unusual dynamic to be one of the most important elements of the risk management infrastructure we needed to build into our practice.

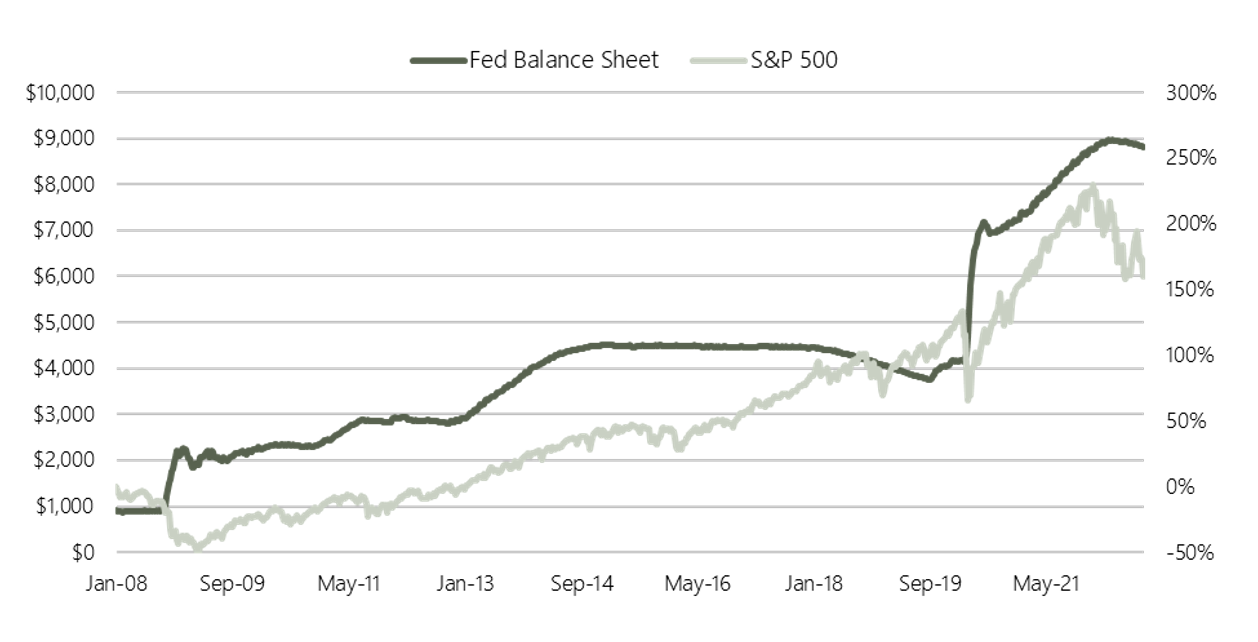

So, what happened? What changed over the course of the past fourteen years, with The Great Recession seemingly reflecting the inflection point in the process? We think the answer lies in the extraordinary levels of fiscal and monetary intervention in the economy and markets (in the U.S. and globally), a development that notably was accelerated as part of the response to The Great Financial Crisis of 2008. Consider that the size of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet in early 2008 was roughly $1 trillion. Within two years, it had more than doubled, and within six years, it had quadrupled, before leveling off and then declining in the period just prior to COVID. Of course, the pandemic brought with it a re-escalation of stimulus measures, on an unprecedented scale, to the point whereby in late 2021, the Fed’s balance sheet, at roughly $9 trillion, stood at a whopping 9x the level of early 2008.

In the chart below (Exhibit I), note also the corresponding performance of the S&P 500 over this same period; the (mostly) upward trajectory of the market is almost a mirror image of the size of the Fed’s balance sheet. What assets was the Fed purchasing over this period? Financial assets, which, of course, are the driving engine of bank balance sheets, while extraordinary levels of excess liquidity were parked on the liability side of bank balance sheets, resulting in distortions for sure, relative to prior periods, notably in the form of exceedingly low funding costs. But the more important connection we think is simply that the Fed was buying financial assets, effectively providing support for asset prices generally, with implications for risk-taking, equity and fixed income markets, and, of course, extreme sensitivity for those sectors of the economy – notably banks – that primarily traffic in these financial assets.

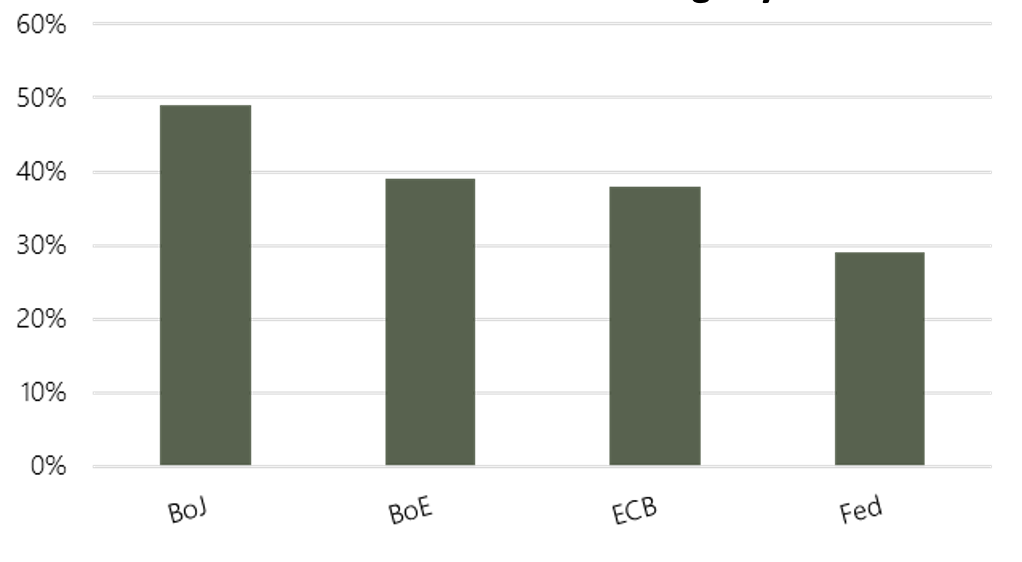

Also consider (see Exhibit II) that the Bank of Japan, Bank of England, European Central Bank, and the Federal Reserve now hold nearly 50%, 40%, 40%, and 30% of their country’s respective government-issued bonds. As we saw with the market turmoil last week involving the Bank of England’s decision to resume Quantitative Easing (or bond buying for short), as central banks and governments become increasingly involved in markets, their decisions reverberate across markets in ways that ultimately dwarf the actions of individual market participants and whole sectors of the economy. Market distortions are such that bank stock prices will move far more on central bank actions than they will, for instance, on news that an individual bank’s net interest margin will be up or down 20 basis points in the upcoming quarter.

Exhibit I: Fed Balance Sheet Vs. S&P 500 Performance

Exhibit II: % Of Government Bond Holdings by Central Banks

What if the historical construct for analysis is now less valid?

Circling back to the original point, it would seem to us that bankers and investors are seeking answers from each other based on a historical construct of how markets tend to perform in relation to sector fundamentals and other indicators that are now less valid. Based on the positive fundamental feedback they are providing, bankers seem to believe the investors are overly pessimistic, whereas the investors think there must be a fly in the fundamental ointment to justify the very real and foreboding strains in the market.

We think the reality is that the fraying linkage between the on-the-ground fundamental reality and market action that is increasingly governed by these non-traditional forces is the primary culprit. In this new reality, we see a plausible scenario whereby banks continue to perform well fundamentally, while equity markets remain under severe strain or worse. Now, over long periods of time, we still believe that strong fundamental performance will correlate to market performance, particularly for banks if these prove to be market rather than credit events. But in the near-term, given the unprecedented set of consideration at hand, we suspect it’s going to remain anybody’s guess as to how it plays out.

Joe Fenech is the Managing Principal of SMBT Consulting, LLC, which provides consulting services to banks. The article represents the views and beliefs of Mr. Fenech and does not purport to be complete. The information in this article is provided to you as of the dates indicated and the data and facts presented herein may change. You should not rely on this article as the basis upon which to make an investment decision; this article is not intended to provide, and should not be relied upon for, tax, legal, accounting or investment advice. Mr. Fenech is also the Chief Investment Officer and Managing Member of GenOpp Capital Management LLC, an investment adviser that maintains exempt reporting status in the State of Indiana. Affiliates of SMBT Consulting, LLC may recommend to such affiliates’ clients the purchase or sale of securities of companies discussed in articles published by SMBT Consulting, LLC.