Community banks are intrinsically woven into the fabric of American society. They provide an array of valuable services, not the least of which includes being the financial catalyst for a large percentage of the small businesses that power American ingenuity and the economy as a whole.

Just ask the neighborhoods in which these bankers serve every day. According to the Independent Community Bankers of America (ICBA), community banks serve as the sole physical banking presence in nearly 33% of U.S. counties. And community banks surpass large financial institutions in the average number of banks operating in both rural and urban markets by a ratio of 3:1, as per ICBA data.

Yet, it is not a stretch to proclaim community bankers are fighting for freedom — financial freedom. Not too many sectors of the economy have achieved the same preservation of generational legacies that community banking has. And yet, the very independence that sets community banking apart is now being challenged like never before amid a perfect storm of prickly regulation, fintech competition, and what one banker described as “pandemic fatigue.”

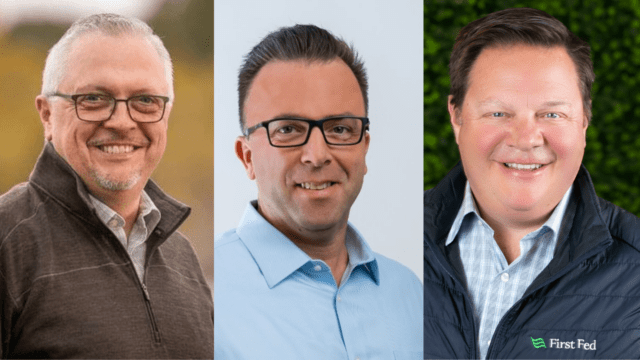

With America’s holiday, the Fourth of July, upon us, we did not want to miss the chance to spotlight a handful of community banks that are on the front lines of the independence movement. Travillian had the privilege to speak with Heartland Bank in Whitehall, Ohio, Village Bank in Saint Francis, Minn., and The Fountain Trust Company in Covington, Ind., each of which shared what independence means to them. While these banks may be structured differently, there is one common thread shared among them and that is their steadfastness, come what may, to protect their independence.

Heartland Bank: Independence in the Buckeye State

Heartland Bank CEO Scott McComb knows something about independence, and he also knows a thing or two about M&A. While these might seem like opposing forces, in some cases, you can’t have one without the other. Just ask Heartland.

Scott’s father, Tiney McComb, founded Heartland Bank in 1988 through a series of chess moves that culminated in the acquisition of a small bank in Central Ohio. Prior to that, Tiney was the top local banking officer at Columbus-based Society Bank, which itself was the product of M&A and is the modern-day Key Bank. It was here that Tiney’s community banking career would take off.

While working at Society Bank in 1987 in Columbus, Tiney spotted The Croton Bank, whose headquarters were in a Central Ohio ghost town that didn’t even warrant a stoplight. However, that town was strategically located next to Johnstown, Ohio, the same city where Intel is currently building its latest semiconductor plant. Even then, Tiney saw an opportunity to gain market share in a region whose economy was coming into its own. His then employer didn’t see things through the same lens, so Tiney decided to take matters into his own hands.

After raising $6.5 million, he proceeded to launch a bank holding company, Heartland BancCorp, that would ultimately purchase Croton. Today that bank is known as Heartland Bank, and its assets currently hover at approximately $1.5 billion. Clearly, Tiney’s prescience paid off in spades, with Heartland going head-to-head with the likes of Huntington, Chase, Fifth Third, and KeyBank, to name a few banks.

Scott is an entrepreneur in his own right, having started several of his own businesses along the way. In 2008, nearly two decades after joining Heartland as a janitor, a job that at the time paid the mortgage, he took the reins from his father, becoming CEO of a publicly traded bank that trades on the OTCQX market. The McComb family controls roughly 12% of the bank, which Scott explains sets it apart from other family-owned banks, where he says management could get away with making an ROE of 6% forever if they were dead set on it.

Scott is an entrepreneur in his own right, having started several of his own businesses along the way. In 2008, nearly two decades after joining Heartland as a janitor, a job that at the time paid the mortgage, he took the reins from his father, becoming CEO of a publicly traded bank that trades on the OTCQX market. The McComb family controls roughly 12% of the bank, which Scott explains sets it apart from other family-owned banks, where he says management could get away with making an ROE of 6% forever if they were dead set on it.

“So, it’s very different being in my shoes. We’re publicly traded, and we don’t control the lion’s share of the shares of the bank. Nobody does, which is a good thing. So, we have to market perform in order to earn our independence. Just like Congress in 1776, until they gained independence, had to earn it; they had to fight for it every day. And banks that are not family-owned have to fight for their independence, too. And it’s no different than the days of the founding of our country,” said Scott.

The hills of Valley Forge, among the Continental Army’s major battles, just happen to be where Travillian’s offices are perched. Valley Forge, a turning point in the Revolutionary War, remains a symbol of perseverance to this day and a place from which community banks can draw fortitude, something they seem to need now more than ever before.

“We consciously made a decision that if we can continue to perform at a certain level, then we earn that independence. I make no bones about that with all our staff, directors, and shareholders. If we trip up, there’s plenty of other people that would love to step in and pay a premium for our institution. But we would lose our independence,” said Scott.

And losing its independence is something that Heartland is not wanting to do.

“If we weren’t performing at the level we are performing, because of our location, because we’re the largest independent bank in the 13th largest city in the nation, we would be No. 1 on 50 other banks’ radars to buy. And so far, the only reason why we haven’t sold is our directors have said, ‘Wait a minute. We have an overall return of around 12-14% annually. What else are we going to do with our money? First of all, who could afford to buy us? And where are our shareholders going to do anything better?’” he said.

So, with consolidation ripe in the community banking space, why do so many banks roll over? Scott says the reason why M&A has persisted in the banking industry is that so many banks lose their fight. They may have thrown in the towel for one of several reasons, including aging directors and shareholders whose main concern has become scoring an acquisition premium.

“They put their money in the bank long ago. They had a good ride but say, ‘Man, I’m ready for that bump,’ and that’s what causes people to sell their institution,” he explained.

A CEO might not own a larger stake in the bank and the only way they can earn a payout is if there’s a change in the control payment on the sale of the bank. However, most of the time, it comes down to forces outside of their control.

“Frankly, I think probably the largest factor is it’s really, really hard to compete on an unfair playing field,” said Scott, pointing to Capitol Hill, where Congress recently gave credit unions the green light to raise capital and expand into business lending.

He continued: “So now we have non-profit competitors right across the street that are acting as community banks that have a 21% head start by not paying Federal tax.”

In addition to these pressures, there are other headwinds, such as the advent of fintechs, big banks getting bigger, the pandemic, and digital currencies, all of which have caused “a ton of fatigue” and fueled M&A, according to Scott, who offered the following advice:

“You have to fight every day to stay independent. Family banks can just call their shots. If they want to stay independent, they can stick a flag in the ground and say, ‘We’re not for sale, we’re going to stay independent.’”

“You have to fight every day to stay independent. Family banks can just call their shots. If they want to stay independent, they can stick a flag in the ground and say, ‘We’re not for sale, we’re going to stay independent.’”

While it might be easier said than done, Scott channels It’s a Wonderful Life’s George Bailey, saying.

“I would guess the fact is that many of my community bank brothers and sisters don’t believe enough in themselves. We can move mountains. Community banks can really do anything for their clients that they set their minds to. And the one thing that they don’t promote enough is the value that they create through the relationships that they have with their clients.”

Village Bank: “The Bank that Don Built”

Saint Francis, Minn.-based Village Bank was founded by entrepreneur Don Kveton close to 30 years ago. He started the bank not because he was a banker but because he is an entrepreneur, explained Aleesha Webb, Village Bank’s president and vice chair.

Aleesha, who is also Don’s daughter, shared with Travillian how as a kid, her dad didn’t even like bankers. And for good reason. He is still haunted by a memory from his childhood of a banker coming to the door and telling his father, who had fallen behind on payments, that the bank was planning to take the farm away from him.

“They were not just taking the farm. They were taking the family home,” said Aleesha.

Even today, running a bank with $500 million in total assets, Don gets uncomfortable when anyone shows up to meet him wearing a tie.

“His vision in starting a bank was to help that entrepreneur and the underdog who had a vision and wasn’t afraid to earn it,” Aleesha said. “Now 30 years later, Don is continuing to help the guy or gal on Main Street who needs a partner and an ally to get there.”

For her part, Aleesha has worked at other community banks and with great bankers along the way in her career. Upon returning to Village Bank, she says it is an honor to come home and serve “the great bank that Don built,” adding:

“Being independent is a responsibility that all of us take very seriously. I do think as we have large banks join our market, independence is getting more difficult — not impossible though. It’s up to us to build those relationships and trust with clients and to really focus on what we are good at, and that’s the local entrepreneur.”

As a family-owned bank, independence is critically important to both Village Bank and the family that owns it.

“Not just to my family, but to all the families at our Village. We have to model that as a community bank. We don’t just care about ourselves, we care about our community,” she said.

Aleesha draws a connection between Village Bank’s independence and its role in helping Main Street businesses that bank with them. She says that then helps other local businesses, triggering a ripple effect in the community they are serving and reaching the families and children they are raising in the Twin Cities area.

“As decision-makers at a community bank, we live down the road from clients. Our kids go to school with Villagers’ kids. These decisions are important and there is purpose behind them. We are not sitting somewhere out on a coast or in a downtown high-rise. We’re not outside this market building a box that people in the Midwest must adhere to. My kids are living near my customers’ kids. We feel the impact of every yes, every no, and every not right now,” Aleesha said. “Independence is truly special because we can help build the community.”

Aleesha describes herself as a glass-half-full person who finds opportunity even in the most difficult of circumstances.

“You have to earn it, dig for it,” she says.

It is getting increasingly difficult for community banks to do so, especially as credit unions get comfortable on their turf. Aleesha describes a scenario in which a credit union might move to Minnesota and attempt to buy a bank charter only to be denied. If they then decide to buy bank branches and assets instead, it hurts everyone. She explained:

“They don’t pay taxes. And perhaps more importantly, they end up treating the entrepreneur differently and don’t take care of the employees of the previous bank. To me, that is an uneven playing field. You can’t give one guy sandals and then give me tennis shoes and ask us to run a race. It doesn’t work.”

The tax component is also vital.

“Our bank pays a lot of money in taxes. We are comfortable with that because we know it’s going back to our state, city, and country. But you’ve got to have competitors doing the same thing. Otherwise, we’ll find it difficult to compete with them in areas like payroll because we are paying that money out in taxes,” explained Aleesha.

She notes that M&A between banks is “great” and is one of the building blocks of bank independence.

The Fountain Trust Company: What Independence Means for Hoosiers

The Fountain Trust Company was founded in the early 1900s in Covington, Ind., which happened to be about the same time that William Nelson White, a local hog farmer, decided to enroll in law school. William’s career change took place after his wife, Mary Emily, had an experience that would alter the trajectory of their family for generations to come.

“My great grandmother got hog slop down boot and swore that would be the last hog she would ever slop,” explained Lucas White, William’s great-grandson and president of The Fountain Trust Company.

For the next three decades, the elder White would practice law. As an attorney during the Great Depression, before the FDIC even existed, he would witness the closure of a number of failed banks in the state of Indiana alone, making an indelible impression on him and changing the family’s destiny once again.

For the next three decades, the elder White would practice law. As an attorney during the Great Depression, before the FDIC even existed, he would witness the closure of a number of failed banks in the state of Indiana alone, making an indelible impression on him and changing the family’s destiny once again.

“That was my great grandfather’s exposure to banking, how he got into banking,” said Lucas.

It wasn’t long before William started buying shares and eventually gained control of the bank. Four generations later, The Fountain Trust Company remains family-owned, with Lucas’ father Kip White at the helm as chairman and CEO.

“All our shareholders fit on a single page of paper. Our bank is about as tightly held as you can be unless it were owned by one person,” Lucas told Travillian.

Like Heartland Bank, Fountain Trust’s independence story also has an M&A component to it.

“M&A is one way to remain independent,” said Lucas. “We’ve been on the acquisition side of that equation two times in the past five years to maintain our independence. One of our goals is to grow the bank enough to keep the next generation of shareholders happy.”

As the former chairman of the Indiana Bankers Association, Lucas described how he used to travel across Indiana to visit every bank in the state. It was then that he carried out conversations with other bankers about the differences between family owned and publicly traded banks, saying many of those bankers could not imagine running a family-owned financial institution while he felt the same way about publicly traded ones.

Lucas agrees with Scott McComb on the Heartland Bank chief’s assessment of family-owned banks vs. publicly traded ones.

“I think at least to a certain extent he’s right,” Lucas said. “It’s what you’re used to. We have much longer time horizons. My goal is to get the bank down to the next generation and then the next generation can decide what to do with it,” Lucas said.

He goes on to say that closely held banks out there whose goal it is to attain a certain dividend level, 15% ROE, or some other metric might be making it harder to remain independent. At Fountain Trust, keeping everyone happy is not about topping earnings year after year or increasing EPS by a certain amount.

“My family is more concerned with the stability, safety, and longevity of the bank as opposed to this quarter’s earnings.”

Those forces all play into Fountain Trust’s independence. Lucas says bank independence touches on everything that Fountain Trust holds dear. With $600 million in total assets, Fountain Trust has 16 locations in Indiana, which is many more than most banks of the same size. Many of these branches are domiciled in very small towns.

Those forces all play into Fountain Trust’s independence. Lucas says bank independence touches on everything that Fountain Trust holds dear. With $600 million in total assets, Fountain Trust has 16 locations in Indiana, which is many more than most banks of the same size. Many of these branches are domiciled in very small towns.

“We figured out how to make them profitable, and that allows us to stay. Our hours are longer than the post office in one of those towns,” Lucas said, underscoring how much these towns depend on the bank.

And Fountain Trust has another 100+ reasons to fight for its independence — its full-time employees.

“If we didn’t maintain our independence, probably half of those people would lose their jobs. So, it’s not only our family and the community but also our employees, many of whom have worked here a long time. If we couldn’t maintain the independence of the bank, a lot of those people would be out of a job,” said Lucas.

Fortunately, Lucas and his family have no intention of letting the bank’s independence slip away. However, the bank president admits it would be nice if the government would do something to make it easier for community banks to stay independent, like passing the SAFE Banking Act, which would pave the way for cannabis banking.

“Everything they do or don’t do, the result is the same, and that is it always makes it harder,” Lucas said.

Credit unions are yet another thorn in their side. Fountain Trust competes with one in Lafayette, Ind., where there is already a fierce rivalry between the Boilermakers and the Hoosiers.

“The credit union out there can do bigger commercial deals than we do,” said Lucas.

While credit unions aren’t Fountain Trust’s biggest concern, they are affecting Indiana’s banking landscape. In a 12-18 month stretch several years ago, five banks sold to credit unions in the state.

“For all five of those banks, there would have been another community bank interested in buying them. A credit union could pay more and paid so much that they got exclusivity on the deal,” said Lucas.

We would like to thank Heartland Bank’s Scott, Village Bank’s Aleesha, and The Fountain Trust Company’s Lucas for sharing their ideas on community banking independence with Travillian.